Fascinating Padre Skinner: Faith, Fastidious Care and Christmas Courage

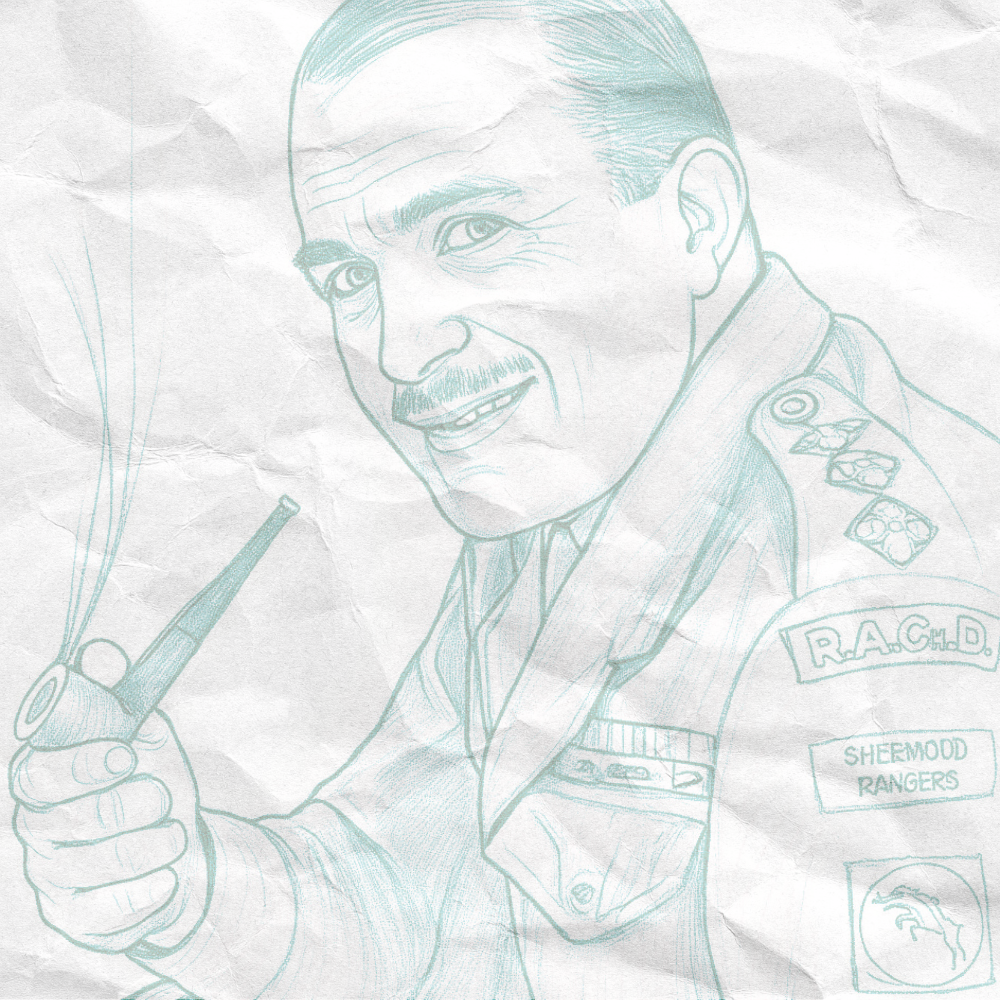

A Christmas season portrait of Padre Leslie Skinner, Sherwood Rangers Yeomanry: a chaplain of faith, fastidious care, and selfless courage.

Spiritual strength under fire: how the Padre kept men human

Christmas is a time for reflection, and and the season of good will. It good me thinking about all the people who inspire me, past and present. In 1944, the men of the Sherwood Rangers Yeomanry had their own spirtual leader, Padre Leslie Skinner.

By December, the Sherwood Rangers were far from the ceremonial idea of war. The frost did not announce itself. It simply arrived, as if someone had poured cold water over the map of Europe and left it to set. This was the working version. Mud that clung like an argument. Ditches that swallowed tank tracks. Nights so dark they felt thick. Somewhere behind them were the beaches and the first awful days in Normandy. Ahead was Germany, and the long, grinding certainty that the job would only be finished by men who kept turning up.

The tanks stood in leaguer like hulking animals, steaming softly, their metal skins ticking as they cooled. Canvas flapped. Engines coughed. Men smoked pipes. Someone swore, not with anger, but as a kind of punctuation.

And then Padre Lesley Skinner appeared, moving through it all with the particular purpose of a man who refused to be merely present.

He was a chaplain, yes, but not the decorative sort. Not a man who arrived for the hymn and left before the hard parts. He had landed with them, under fire, on D-Day. He had dragged wounded men to safety, as if his stole were made for lifting.

Now, in the build up to Christmas, he did what he always did.

He worked.

His kit was simple: a small bundle of paper, a pencil that never seemed to run out, and a battered book of prayers that had learned the smell of cordite. The mythical version of the story says he carried a lamp like Nightingale. The real version is more interesting. He carried attention, and attention is rarer than light.

He stopped first at the cookhouse, not for a brew, but to check the arrangements.

“What are we feeding the lads?” he asked.

Trooper Arthur Reddish started to explain shortages, supply chains, the usual excuses the war had perfected.

Skinner nodded, listened, and then asked again, slightly differently, which was his way. He did not browbeat. He simply refused to accept that a problem was the same thing as a conclusion.

It is a quiet kind of fastidiousness, the sort that looks like fussing until you realise it is actually love, given structure.

He made a circuit of the leaguer, head inclined, as if listening. Deafness had been his companion for much of his life, but it had not softened his ability to notice. If anything, it had sharpened it. The way a man’s hands shook as he rolled a cigarette. The way another man avoided looking at a certain empty place where a crew should have been.

Skinner did not ask the men to be brave in the abstract. He asked for specific things.

Wash your hands before you eat.

Boil the water.

Open the tent flap when the stove has been burning too long.

Air the blankets when you can.

Small obediences. The sort that kept sickness at bay and kept men feeling human.

In the myth, the wind itself obeyed him. In truth, it was the men who did. Not because he had rank to command them, but because he had earned the right to be taken seriously. He had been there when it mattered, and he was still there now.

A trooper called out, half joking, “Padre, are we getting Christmas off then?”

Skinner gave him a look that held both amusement and the weight of reality.

“You can have Christmas,” he said. “You can even have joy. But you can’t have a day off from being decent.”

That was his trick, if you can call it that. He made decency feel like something robust, not sentimental.

Later, as the light fell away and the cold tightened, he went to the edge of the leaguer where the recovery crews worked. The war had a habit of leaving difficult tasks for the end of the day, and this was one of them.

He had a rule, and he held to it. Tank crews were not to be made to climb back into the wreckage of their own knocked out vehicles to retrieve the dead. If the regiment needed someone to do that work, it would be him.

In the mythical telling, angels walk beside him when he goes out. In the real world, it was often just him and the cold and the awful silence that arrives after the fighting has moved on.

He returned, eventually, with his coat smelling of smoke and earth. He said little. He did not turn it into theatre. He did not offer the men a story they could applaud and forget.

Instead he sat on an upturned jerry can, took out his notebook, and began to write.

Not operational details. Not glory.

Names.

Units.

Locations.

Personal effects.

Where a man was buried, and how to find him again.

He kept records because memory is a form of respect, and because grief becomes unbearable when it has nowhere accurate to land.

Then he wrote letters. Not the stiff kind that sounded like the Army, but the kind that sounded like a man who had looked after someone at the end and wanted their mother to know they were not alone. He did this again and again, and in time those letters became a correspondence that lasted well beyond the war.

Christmas Eve came with the same weather and the same danger. No choir. No safe streets. No certainty.

Skinner gathered the men where he could, in a barn that smelled of animals and damp straw, or in the lee of a tank, or in the cramped warmth of a turret. He did not demand piety. He offered a moment.

A few words. A prayer said plainly, without forcing emotion.

He spoke of light, because everyone understood light. He spoke of home, but carefully, because home could bruise. He spoke of forgiveness, because men at war collect things that need forgiving. He spoke of duty, not as a slogan, but as a way to carry yourself when fear is trying to shrink you.

And then, because he was Skinner, he did something practical.

He made sure the lads ate.

He checked the sick.

He walked the line one more time.

The world likes its heroes clean and simple, lit like statues. Padre Skinner was something better. A man of faith who treated the body as worth protecting and the soul as worth tending. A man who believed in the sacredness of small things, done properly.

A man who did not put himself first, even when nobody would have blamed him for doing so.

It is fashionable to talk about values. He lived them, in mud, in winter, in the push to finish a war that had already taken too much.

And if you listen closely, in the myth and in the record, you hear the same message.

Hope is not a feeling.

It is work.

Historical note (for context): Rev Leslie Skinner was a Methodist minister and Army chaplain attached to the Sherwood Rangers Yeomanry, recorded as being among the earliest chaplains ashore on D-Day with the regiment on Gold Beach. His wartime diary and papers are held by the Imperial War Museums, including a diary covering June 1944 to May 1945 and a casualty book recording burials.

Thank you for visiting Field Notes for Modern Life.