Zeno: A Principled Man That Built an Unparalleled Philosophy

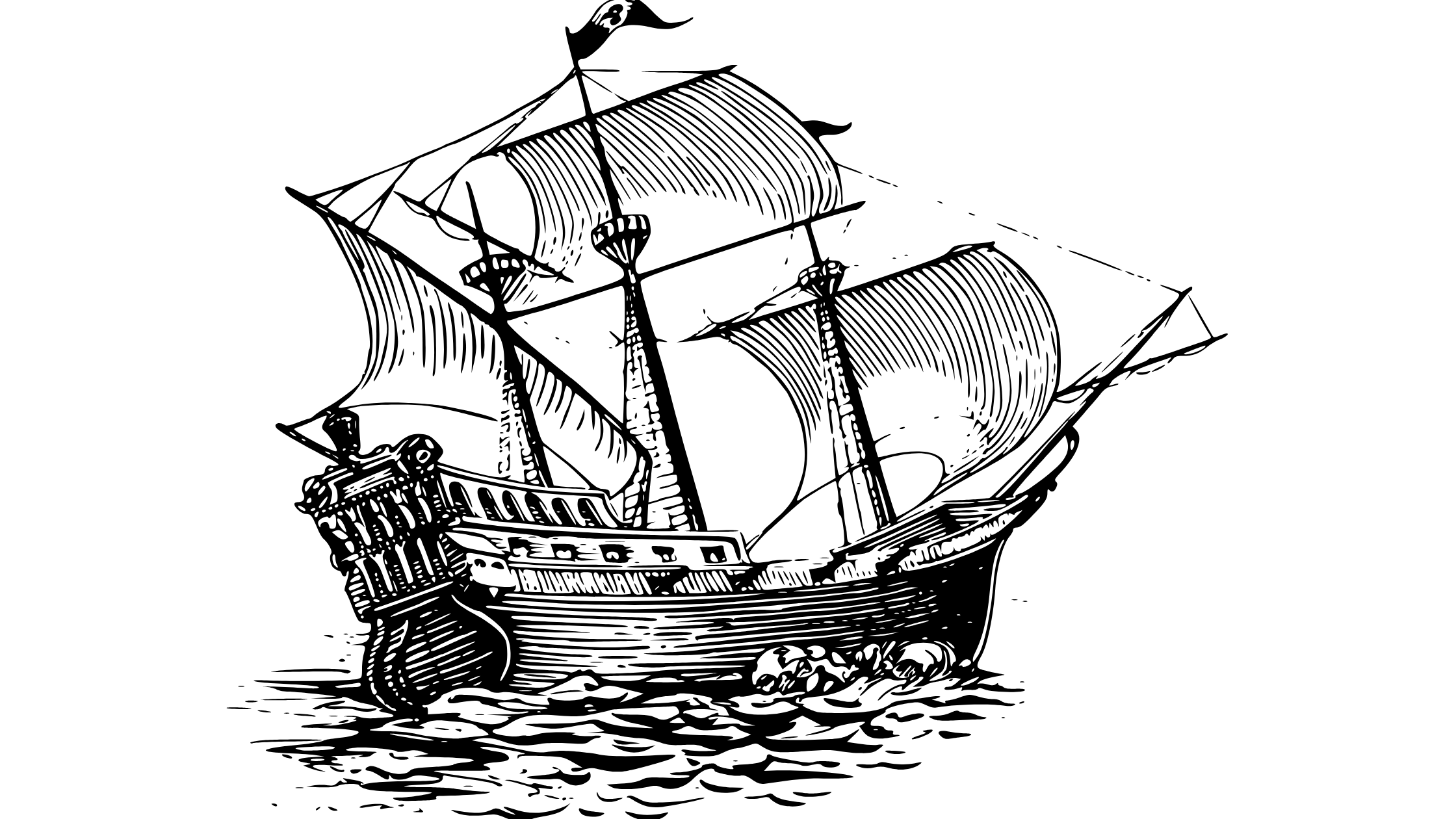

A mythical portrait of Zeno of Citium in Athens, showing how Stoicism turns hardship into clarity, character, and calm in a noisy world.

A mythical walk through Athens with the father of Stoicism

This post is the third in a small Christmas trio for Field Notes for Modern Life, on faith, spirituality, and philosophy. Not the shiny version that lives in cards and carols, or the commercial chaos that Christmas brings today. This is about the habits that steady us when life is loud. In the other articles, Florence Nightingale brings practical compassion to a winter ward, and Padre Leslie Skinner carries faith through the mud and danger of the Allied push into Germany. Here, we step further back in time to Athens, and to Zeno of Citium, whose answer to hardship was not comfort, but clarity.

The story begins the way most useful philosophies begin, with a loss that cannot be negotiated with

A ship goes down. A life plan goes with it. The sea does what the sea does, and a man ends up onshore with wet clothes, feeling shaken, a lighter purse, and the uncomfortable realisation that the future will not be taking instructions.

The man is Zeno of Citium. In the retelling, the details shift with the storyteller, but the shape of it holds. Something breaks. He survives. He arrives in Athens with nothing he can cling to except his own mind, and the mind, as he is about to discover, is both the problem and the solution.

Athens is loud, even when it is not shouting. It is a city of opinions. Of arguments thrown like dice. Of men selling certainty from street corners. Of teachers with pupils, pupils with egos, and egos with pupils.

Zeno walks through it as if he is looking for a door that is not obvious.

He finds it, not as a doorway, but as a habit. A place where people gather. A colonnade. The Stoa. Shade in summer, shelter in winter, and a steady stream of human life passing through, carrying its usual cargo, pride, fear, ambition, grief, hunger, loneliness.

He stands there and watches.

Not like a tourist. Like a man taking notes on what hurts people.

A young man approaches first, full of energy and raw certainty. He speaks quickly, as if speed proves truth.

“What should I do if I want to be happy?” he asks.

Zeno looks at him with the mild patience of someone who has seen a ship vanish beneath him and has decided to stop pretending the world is a customer service desk.

“You should decide what you mean by happy,” he says. “If you mean comfort, you will be frightened whenever the wind changes. If you mean character, you can begin today.”

The young man frowns, because this is not the answer he wanted. It does not sparkle. It does not flatter.

Zeno continues anyway.

“Most people want peace while keeping the habits that ruin peace. They want calm without discipline. They want freedom without self control. They want life to stop being life.”

He does not say it harshly. He says it as a man describing weather.

A woman pauses nearby, listening. Her hands are red from work. She has the look of someone who carries a household and a set of worries at the same time.

“What if life is simply too much?” she asks, half to herself.

Zeno shifts his weight, and for a moment you can see the merchant he once was, the man who understood accounts and cargo and risk. He does not dismiss her question as weakness. He respects it.

“Then we sort it,” he replies. “Not all of it. Not at once. We take what is ours to carry, and we put down what is not.”

This is the heart of him, the clean dividing line.

Some things are up to you. Many things are not.

Your choices, your attention, your honesty, your restraint, your courage, your kindness, your willingness to do the next right thing. These belong to you.

The weather, the gossip, the market, the illness, the moods of other people, the accidents of history. These do not.

Zeno gestures to the city beyond the Stoa, to the swirl of Athens doing what Athens does.

“Do you see them?” he says. “They are running about trying to control the sea. That is why they are tired.”

A soldier limps past, one arm held awkwardly, a face set in the stubborn mask men wear when pain has become ordinary. He stops when he sees Zeno, not because he believes in philosophers, but because he recognises someone who does not waste words.

“What’s the point of virtue,” he asks, “if the world is still cruel?”

Zeno studies him for a second, then answers in the simplest way.

“Virtue is the one thing cruelty cannot steal.”

The soldier looks down, as if that sentence has landed somewhere he did not expect.

Zeno does not offer false comfort. Stoicism is not a lullaby. It is closer to a hand on the shoulder and a reminder to stand up straight.

“The world will do what it does,” he says. “Your task is to meet it as the best version of yourself. Not perfect. Not unbreakable. Just honest, and awake.”

This is where the myth begins to grow, like a Cedar tree rising out of the mud.

In the stories, the Stoa becomes more than a porch. It becomes a workshop. A place where people bring their lives as they are, messy and stubborn and full of excuses, and Zeno teaches them how to stop making things worse.

He teaches them to watch their impressions, those first flashes of judgement that arrive before thought. He teaches them to pause before agreeing with every anxious story their mind tells them. He teaches them to ask, quietly but repeatedly, “Is this true, or is this panic dressed up as certainty?”

He teaches them that emotions are not enemies, but they are not always reliable guides either. A feeling is a signal, not a verdict. You can listen without obeying.

He teaches them to live according to nature, which sounds lofty until you realise it means something very plain. Live as the sort of creature you are. A social animal. A reasoning animal. A being capable of choosing decency even when nobody is watching.

There is also a spiritual note to it, even if it is not church shaped.

Zeno speaks of a universe with order, of a rational thread running through things. He does not promise that life will be kind. He suggests that it will be meaningful when you align yourself with what is good, rather than what is easy.

In this way, Stoicism becomes a kind of faith without sentimentality.

Not faith as wishful thinking, but faith as practice.

The belief that you can be steady.

The belief that you can be useful.

The belief that your character is worth building, even in a collapsing world.

A man arrives late one afternoon, breathless, face shiny with the sweat of fear.

“I’ve lost everything,” he says. “My business, my standing, my friends, all of it. It’s over.”

Zeno tilts his head, and the slightest hint of humour appears, not cruel, just human.

“Welcome,” he says. “You are now in the perfect position to begin.”

The man stares, offended.

Zeno holds his gaze.

“If you were only ever good when life applauded, you were never good. You were simply performing. Now we can find out who you are.”

There are people who hear that and turn away. Stoicism is not for those who want a philosophy that lets them keep their favourite illusions. It asks for honesty. It asks for self command. It asks you to be responsible for your inner life.

It does not ask you to be a robot. It asks you to be a grown up. Agnostic of technology.

And that is why Stoicism it still matters.

Because we live in an age of constant provocation. Outrage on tap. Fear sold as a service. Attention harvested like a crop. A thousand little pressures pushing us to react, to posture, to perform. It is exhausting.

Zeno would look at the modern world and recognise the same old problems in brighter packaging.

He would not tell you to retreat from life. He would tell you to enter it properly.

To turn urn off the news.

To put down your phone.

To be calm without being passive.

To be disciplined without being harsh.

To put others first without turning yourself into a doormat.

To accept what you cannot change, and to work, steadily, on what you can.

That is not ancient trivia. It is survival.

So if you want a mythical image to hold onto, keep this one.

A man under a colonnade in Athens, not selling comfort, not shouting, not seeking followers for his own ego. Just teaching people to stop being bullied by their own minds. Teaching them to live as if character is real, and worth the cost.

The world still needs people like that.

Not perfect sages.

Just people who practise steadiness, and make it contagious.

One question for you: What is one thing you are carrying right now that is not actually yours to carry?

Before we wrap up this post, think of Zeno, Nightingale and Skinner, and ask what virtues they bring to the 21st century. When you look closely, they are all still appropriate for modern society.